Germany's Spiritual Heroes by Anselm Kiefer in the light of three art historical perspectives

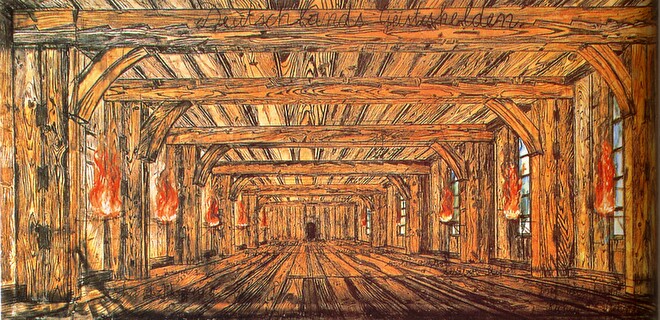

The wooden attic in Anselm Kiefer's painting Germany's Spiritual Hero's looks very flammable, thanks to rows of burning torches on the walls, but there is no fire, at least not yet.

Anselm Kiefer, Germany's Spiritual Heroes, 1973, oil and charcoal on burlap, mounted on canvas (307 x 682 cm), Santa Monica, © 2009 Anselm Kiefer, Photo courtesy of The Broad Art Foundation, photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles (fig.1).

Deutschland Geisteshelden is written in black charcoal on the top beam. The names of German intellectual heroes, including Wagner's, are written on several wooden planks. The Wagnerian spirit is the spirit of victory, but tainted by WWII, like other German hero names. Historian Andreas Huyssen writes that one immediately sees that Anselm Kiefer works with myths and history.[1] According to Huyssen, Kiefer tries to find his position as an artist between thoughts of the end of art and the defeat of fascism. Materials have transformative meanings for Kiefer. He adopted these meanings from his teacher Joseph Beuys. In their works of art, fire represents transformation, passing over. The wood represents German culture. [2] Anselm Kiefer was an intellectual who grew up in the culture of post-war Germany that was struggling with the identity crisis after everything the Nazis had done. In search of his own identity in Germany's past, he looked for materials and visual resources with a transformative character.[3]

Kiefer's choice of visual media in Germany's Spiritual Heroes in the light of Gombrich's visual convention theory and Alper's theory of visual culture

Gombrich argued that the artist depicts reality using inherited visual conventions. According to him, the history of art builds on the fact that every new artist tries to add something new to these conventions. The way people see art or make art depends on their experiences, practices, attitudes and interests. According to Gombrich, perception is not given, but a learned trait. He talks about image conventions and looks strongly from the perspective of an artist. Gombrich wants that when analyzing an artist, one should focus on the moment when the artist was active.[4]

Kiefer searched for his German identity through visual means and myths that were deeply ingrained in German culture.[5] Like Gombrich and his teacher Beuys, Kiefer refuses modernist art from New York, seeing it as a rootless form of storytelling about time and place. According to Gombrich, the hidden essence of things could be modeled and constructed. Kiefer attempted to construct the hidden essence of things through symbolism and transformative properties of materials he used in his art. He sought to reinvent traditional figurative forms such as landscape and history painting and used conventional visual means that represented German identity, means that can be traced back to Dürer.[6]

According to Gombrich, a painting is a relative model of reality. Culture determines what is possible. Meaning is not determined in advance but follows the artist's construction from myths. We see that Kiefer reuses many symbolic materials that refer to German culture and mythology. With his book Art and illusion, Gombrich was a precursor of visual culture as a discipline. He understood that under the changed conditions of modernity, any theory of art had to be guided by theory and visual culture[7]. Just like with Gombrich, watching is central to Svetlana Alpers. In her book Art of describing she argues that there must be more than a relationship between form, content and style. It is based on the concept of visual culture. She looks for aspects or elements that are important within a culture. In her book Art of Describing, Alpers described the concept of visual culture in her analysis of 17th-century Dutch art. She named a matrix of seeing and imaging using, for example, optical means. An arsenal of resources appropriate to the artistic culture of that time. Alpers offered an alternative framework to view art from an anthropological perspective. She viewed 17th century art on the basis of five visual impulses, such as the contemporary state of science, knowledge of nature and looking, the artist's representational ability, the ability to map something and the inscription. power.[8]

Kiefer plays with the viewer's perception and knowledge by incorporating visual means into his painting that reflect the visual culture of Germany as a nation. Wood and forests are widely known as symbols of German identity. [9] The names of the German heroes are internationally known, but written in black they refer to death and mourning. Kiefer turns to neo-expressionism, the figurative in his country's culture, for his narratives of German mythology.[10]

Kiefer's Germany's Spiritual Heroes and Clark's social theory

Art by Anselm Kiefer is ideologically charged. He is continuously looking to reinvent German identity. In that context, the theory of T.J. Clark interesting, because according to him formal language is not separate from a socio-political view of the world. In his work Image of the people he argues that art cannot be viewed with an innocent eye, but from a biased perception framework in relation to the ideology from which it emerged. He also writes that the meaning of paintings changes depending on who, when and where they are viewed. [11] “According to Clark, the relationship to the ideology from which they emerged should play a much more important role in the analysis of works of art.” [12] Continental thought at that time was shaped by Marxism and Freudian psychoanalytic thoughts. In an analysis of Courbet's painting the Burial at Ornans, Clark writes that viewers were most bothered by its meaning. The unclear representation of class is the common thread because the villagers depicted wear the clothing of the urban bourgeois. The artist disproves the bourgeois myth about the unbridgeable differences between the countryside and the city. According to Clark, art resists power not through direct opposition but through the undoing of thought structures on which the operation of power rests. Clark speaks of ambiguity in Courbet's work. [13] And that is something we also observe with Kiefer. Kiefer tries to confuse the viewer with his myths misused by the Nazis. He uses German hero names but written with black charcoal, on wooden planks in an attic that looks more like a crematorium. As if Kiefer is trying to purify these names through the transformative power of fire. He gives the myth of German identity a different meaning. As with Clark in his analysis of Courbet's The Burial, Kiefer's ambiguity of meaning attempts to confuse his viewer by taking away the original meaning of the myth. [14]

Anselm Kiefer leaned on the usual German image conventions in his work Germany's spiritual heroes, because in this painting we see symbols that represent German identity, such as wood and names of the German heroes. If we illuminate the painting according to Svetlana Alpers' theory, Kiefer uses the arsenal of cumulative knowledge and skills built up by the artists and philosophers of German history. According to Clark's theory, the choice of images and visual media, including myths, can be viewed from the ideological point of view, from the political position of the country that was searching for its identity after the Second World War.

Kiefer recycles mythology in hopes of rediscovering his identity and returns to the representational power of art in his work. He acts from his ideological convictions and tries to make the viewer think by first confusing them. The latter can best be explained on the basis of Clark's theory.

Literature

Arasse, D. Anselm Kiefer. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2014.

Halbertsma, M, K, Zijlmans. Viewpoints: an introduction to the methods of art history, eds. M. Halbertsma, K. Zijlmans. Nijmegen: Sun, 1993.

Huyssen, A. “Anselm Kiefer: The terror of history, the temptation of myth.” October, 48 (1989): 25-45.

Rampley, M. “In search of cultural history: Anselm Kiefer and ambivalence of modernism”. Oxford University Press: Oxford Art Journal, 23, 1 (2000): 73-96.

Riley, B. “Fire In The Attic: Anselm Kiefer, Poet Of Paradox”. 3 Quarks Daily, 2019.

Saltzman, L. Anselm Kiefer and art after Auschwitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Schama, S. Landscape and memory. London: Harper Collins Publishers, 1996.

Westermann, M. “The art of describing: Dutch art in the seventeen century, 1983. In The books that shaped art history: from Gombrich and Greenberg to Alpers and Krauss, edited by Richard Shone and John-Paul Stonard, 165-175. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

Wood, C.S. “Art and illusion: a study in the psychology of pictorial representation, 1960”. In The books that shaped art history: from Gombrich and Greenberg to Alpers and Krauss, edited by Richard Shone and John-Paul Stonard, 165-175. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

Wright, A. “Image of the people : Gustave Courbet and the 1848 revolution,1973”. In The books that shaped art history: from Gombrich and Greenberg to Alpers and Krauss, edited by Richard Shone and John-Paul Stonard, 165-175. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

Websites consulted

https://imagejournal.org, Image Journal website, Siedell, D.A., “Where Do You Stand? Anselm Kiefer’s Visual and Verbal Artifacts”, Image, Issue 77, accessed December 14, 2021, from https://imagejournal.org/article/where-do-you-stand

[1] Huyssen, “Anselm Kiefer: The terror of history, the temptation of myth”, 41. [2] Saltzman, Anselm Kiefer and art after Auschwitz, 84. [3] Schama, Landscape and memory, 127-129. [4] Wood, “Art and illusion: a study in the psychology of pictorial representation, 1960”, 118. [5] Arasse, Anselm Kiefer, 140. [6] Schama, Landscape and memory, 126-129. [7] Wood, “Art and illusion: a study in the psychology of pictorial representation, 1960”,125. [8] Westermann, “The art of describing Dutch art in the seventeen century, 1983”, 182-184. [9] Schama, Landscape and memory, 129-134. [10] Rampley, “In search of cultural history: Anselm Kiefer and ambivalence of modernism,” 73-96. [11] Wright, “Image of the people : Gustave Courbet and the 1848 revolution,1973”, 166. [12] Halbertsma, Zijlmans. “Viewpoints: an introduction to the methods of art history”, 178. [13] Wright, “Image of the people : Gustave Courbet and the 1848 revolution,1973”, 171. [14] Rampley, “In search of cultural history: Anselm Kiefer and ambivalence of modernism”, 81.

acts from his ideological convictions and tries to make the viewer think by first confusing them. The latter can best be explained on the basis of Clark's theory.

Shopping cart

My Account

Login

Forgotten your password?

No account?

With an account you can order faster and you have an overview of your previous orders.

Create an Account